For an enhanced digital experience, read this story in the ezine.

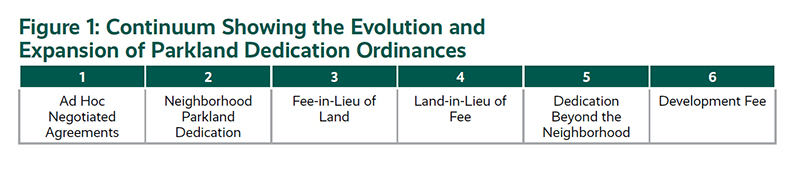

Courts have consistently endorsed and enhanced the principle of communities passing the costs of growth through to new residences that created the costs. The enhancements have led to the emergence of “new normals” manifested by expansion of the types of parks that are eligible, inclusion of development fees, and inclusion of reimbursement clauses. Figure 1 below shows a continuum of the evolution, extension and expansion of parkland dedication ordinances that has occurred over the past half century.

Ad Hoc Agreements

Before the tax revolt of the late 1970s, many cities believed they could achieve more parkland by fostering developer good will through negotiating ad hoc agreements than by mandating it be dedicated. This approach meant the parkland being secured depended on the economics of a development, a developer’s sense of noblesse oblige, local needs, and the aggressiveness and expertise of elected representatives and city officials in negotiating with developers. However, developers frequently are represented by specialist lawyers and consultants whose expertise typically far exceeds that of local city planners, so taxpayers are disadvantaged.

Although a goal of negotiated agreements is to prevent friction with developers, it often creates friction. A principle of good governance is “horizontal equity,” which requires that equals should be treated equally. Since negotiated “donations” are determined on a case-by-case basis, it is likely this principle will be breached with substantially different levels of dedication being exacted for similarly situated developments.

The need for a more sustainable vehicle became apparent in fast growth cities when the political climate and legislative actions emanating from the “tax revolt” of the late 1970s and early 1980s made raising taxes for acquisition and development of park facilities infeasible in many communities. This stimulated the widespread enacting of parkland dedication exactions.

Neighborhood Land Dedication

The earliest approach to replace negotiation with a fixed formula imposed “mandatory dedication” of land for neighborhood parks (Figure 1, stage 2). Developers were required to deed a specified amount of land on their site for a park. However, requiring the dedication be in the form of land meant the size of the acquired land was determined by the size of the developer’s project. Because most projects involved a relatively small acreage, only small, fragmented spaces were provided. They offered limited potential for recreation and were relatively expensive to maintain.

Fee-in-Lieu of Parkland

This limitation encouraged cities to broaden their ordinances to require developers to pay a fee-in-lieu of the fair market value of the land that otherwise would have been dedicated (Figure 1, stage 3). This meant the dedication was no longer confined to a developer’s subdivision, because fees could be spent off-site. The shift to a cash option also enabled cities to expand ordinances beyond acquiring land, so funds could be used to develop improvements on parkland and/or to renovate existing parks.

Parkland-in-Lieu of Fee

Some communities have elected to require payment of fees to be the default norm, and land-in-lieu of a fee payment to be an exception option exercised at the discretion of the city (Figure 1, stage 4). This reflects the reality that a large majority of dedications are in the form of fees rather than land. There are three reasons for this. First, many ordinances specify they will not accept land dedications of, say, less than five acres. Thus, if the level of service for the land dedication is 100 dwelling units per acre, then only projects of at least 500 units will have this option. Second, if cities are “landlocked,” then new growth is primarily going to be infill development, often characterized by higher structures rather than a bigger footprint, so no land is available. Third, cities that have made substantial front-end investment in parks that is intended to meet future needs may require subsequent dedications be in cash to reimburse the costs of those investments.

Dedication for Parks Beyond the Neighborhood

This expansion of dedication requirements (Figure 1, stage 5) recognizes that new residents do not confine their use only to neighborhood parks. The initial focus on neighborhood parks was based on the premise that residents walked or biked to the nearest park. In contemporary society, data frequently show most users are likely to drive to the park that best meets their needs for a desired experience. Selecting a park to visit is usually based on which amenities are desired, rather than which park is closest.

The Emergence of Park Development Fees

The emergence of park improvement fees in the new millennium (Figure 1, stage 6) reflected a realization that providing only land requires existing taxpayers to pay the costs of transforming bare land into a functioning park. Thus, the intent to require new growth to pay the cost of the demands it places on parks is not fulfilled. If a park development fee is not required and the community fails to approve a bond issue to transform raw land into a functioning park, then the result may be desolate open spaces devoid of park-like qualities that are a blight and public nuisance rather than a benefit and positive asset.

Creating Greater Awareness

Although the courts have embraced stages 5 and 6 of Figure 1, relatively few cities have adapted to this trend. Consequently, the unrealized potential of parkland dedication ordinances is arguably the lowest hanging fruit of capital funding sources for parks. Part of the reason for this is that the implementation of the ordinances is the purview of planning departments, not park and recreation departments, since they are a component of a city’s subdivision regulations. Their unrealized potential suggests that park directors should perhaps take a more proactive role in making city managers and elected officials aware of their full potential.

John L. Crompton, Ph.D., is a University Distinguished Professor, Regents Professor and Presidential Professor for Teaching Excellence in the Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Sciences at Texas A&M University and an elected Councilmember for the City of College Station.