It has long been recognized that many people will pay a premium to live close to a park. Indeed, the pioneering urban parks in the mid-1800s were funded by cities that acquired land for a park and retained one-third to one-quarter of the land to sell or lease after the park was completed to pay its capital costs. These early parks were viewed as economically beneficial features that enhanced profits from real estate developments.

Unfortunately, in contemporary times, elected officials rarely recognize the financial merit of parks. Their social merits may be accepted, but conventional belief states that parks are a costly investment from which a community receives no measurable financial return.

However, this perspective overlooks the enhanced property taxes stemming from increased increments of value at properties located close to parks. The principle is illustrated by the hypothetical 50-acre park situated in a suburban community shown in Figure 1 (see gallery below).

It is a natural, resource-oriented park with some appealing topography and vegetation. The cost of acquiring and developing it (fencing, trails, supplementary planting, landscaping, picnic shelters, etc.) is $50,000 an acre, so the total capital cost is $2.5 million. The annual debt payments for a 25-year general obligation bond on $2.5 million at 5 percent are approximately $185,000.

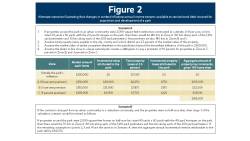

In Figure 2, annual income streams that can be attributed to the park and could service the bond debt are developed based on two different scenarios. Scenario A in Figure 2 shows the annual incremental property taxes in the three zones from the premiums attributable to the park amount to $189,500. This is sufficient to pay the $185,000 annual bond debt

repayment.

Scenario B results in annual property tax increments in the three zones of $94,500. Clearly, changes in any of the four assumptions listed in the scenarios of Figure 2 will lead to different outcomes. Readers are invited to insert numbers into these assumptions that best reflect the context with which they are concerned.

The alternative scenarios in Figure 2 suggest the proximate premium may be less effective in covering costs in suburban (Scenario B) than in urban (Scenario A) areas. In a garden-style suburban neighborhood, a park would provide continuity and reinforce the image of the neighborhood, rather than provide a contrast to its surroundings. However, there will be fewer homes benefiting from proximity to the amenity than in urban areas with denser housing patterns. Thus, if a suburban park is to deliver equivalent tax revenues, either the premium paid by each home must be substantially higher relative to urban contexts, or the cost of land must decrease disproportionably relative to the number of houses around the park.

The Edge Effect

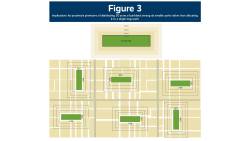

A determining factor of the magnitude of a park’s impact on the property tax base is the extent of the park’s perimeter or edge. This is demonstrated in Figure 3, which suggests the property premium emanating from six 8.33-acre parks, with dimensions of 400 by 100 yards (giving an aggregate perimeter of 1,000 yards per park) and non-overlapping impact zones, will be substantially greater in aggregate than the premium generated by the 1,210 by 200 yards (2,820-yard perimeter) 50-acre park.

The edge effect suggests that narrower lots fronting on to a park create higher aggregate premiums, because more homes benefit from being adjacent to the park.

Proximate Premiums Facilitate Parks, Not Justify Them

Incremental premiums should be part of the debate when considering the cost of amenities. When evaluating optimum land use, the sequence of events should be:

- The decision that a projected park has social merit

- The existence of political will to pursue it

- The exploration of a project’s potential to enhance the tax base, when the central focus shifts to financing it

Stay tuned for the April issue of Parks & Recreation to read more about the financial benefits that parks provide.

John L. Crompton, Ph.D., is a University Distinguished Professor, Regents Professor and Presidential Professor for Teaching Excellence in the Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Sciences at Texas A&M University and an elected Councilmember for the City of College Station.