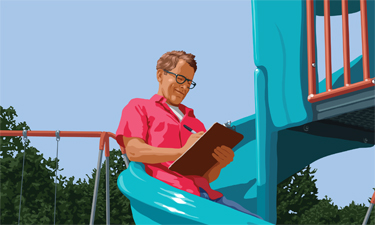

When Tony Malkusak steps onto the playground, it’s a game of I Spy.

When Tony Malkusak steps onto the playground, it’s a game of I Spy.

“I try to take a fair amount of time just to observe, take in the equipment, the space itself, the circulation pattern, and get as much of an understanding of the environment and play space area as possible,” says Malkusak, president and landscape architect at Abundant Playscapes, Inc. in Iowa City, Iowa. He’s among the army of thousands of certified inspectors across the country checking the local play spaces and equipment kids fearlessly climb up, scramble over, and leap from. Questions around playground safety first sparked two decades ago over a contraption known as the Giant Strider—a tall pole with long metal swings attached at the top by ropes or chains. “Basically, those were just used as weapons on the playground,” explains Caroline Smith, playground safety manager at the National Recreation and Park Association.

In 1991, the Giant Strider became the first piece of playground equipment ever recalled by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (which recalls products from baby bottles to trampolines). Soon, other pieces came under scrutiny. “There were these big animal swings that you’d put a little child on, but these were 50 pounds—just too heavy of an object that can be swung at another person,” says Smith, who, as the mother of three boys, knows well kids’ propensity for inventing ways to misuse equipment.

That same year, NRPA partnered with the National Playground Safety Institute to create the Certified Playground Safety Inspector Program (CPSI), which trains inspectors to make sure playgrounds are safe. Certified inspectors can work for government agencies and parks and recreation departments, or be private consultants.

To get certified, inspectors must pass an exam every three years. “There are always innovations in playgrounds—standards will be updated, or new pieces of equipment will come out,” Smith explains.

Playground inspectors such as Malkusak, then, have become defenders of children—scrutinizing bolts, measurements, and cracks to keep kids from preventable harm.

“We’re not trying to eliminate all injuries: Kids fall on the playground, that’s what happens…If you fall the wrong way, it doesn’t matter what you fall on, you can break your arm,” Smith says. “What we try to do is eliminate death and debilitating injuries.”

Sharks and Minnows: Lurking Danger

It’s all fun and games until someone gets hurt: Despite advances in playground equipment and safety measures, the danger at playgrounds is real. Each year from 2001 through 2008, an average of 218,851 preschool and elementary children were taken to the emergency room for playground-related injuries, according to a Consumer Product Safety Commission report. Most commonly, kids’ injuries were fractures (36 percent), contusions/abrasions (20 percent), lacerations (17 percent), and strains/sprains (12 percent).

In addition, some 40 deaths were associated with playground equipment from 2001 to 2008, according to the report. The average age of those killed was six years; the median age was four years. While 27 of the deaths were the result of hangings or other asphyxiations, seven deaths were the result of head or neck injuries. Children were most likely to injured by swings, slides, and climbing structures.

Some 44 percent of playground injuries are due to falling, according to the Commission’s report, a big reason that guidelines state how deep wood chips must be depending on the height of the equipment. “If you have adequate surfacing, you can eliminate a huge amount of injuries,” Smith says. Equipment-related hazards like breaking or assembly mistakes account for another 23 percent. Even normal wear and tear can mean time for a safety check.

For a trained inspector, rooting out hidden danger is all in a day’s work.

“Keep Away” the Hazards

As one of the training faculty members for the CPSI program, Malkusak has trained thousands of certified inspectors across the country.

“Our job is to look for hazards and things that are non-compliant, but ultimately we’re in the business of promoting children’s play,” says Malkusak, who designs and oversees construction of play environments in addition to conducting playground audits and inspections. “We’re making sure things are on the up and up, and what we know can happen—we’re trying to prevent it from happening.”

It’s an inspector’s job to spot possible hazards, but Malkusak has heard tales of overreaction: playgrounds shut down because someone thinks the water fountain is an entanglement hazard or a toilet seat is a possible entrapment hazard.

Though California is the only state that requires playgrounds to be inspected, many states have adopted the Consumer Product Safety Commission standards as voluntary guidelines. These guidelines are based on research by ASTM International (formerly known as the American Society for Testing and Materials), which develops highly technical international voluntary consensus standards for everything from mattresses to tires to playground equipment. The commission writes those standards in a more user-friendly fashion, explains Smith.

Guidelines have evolved with the goal of reducing deaths and debilitating injuries. Sweatshirt hood cords had been found to catch on openings in slides, choking a child; now, inspectors look for small slits where a cord could be pinched. Kids who climb swing sets to go across the top have been strangled by their sweatshirt hoods that snag on upward-facing bolts when they jump down; now inspectors pay attention to which way bolts are facing.

Over time, these lessons learned and additional research have helped inspectors to spot dangers that aren’t obvious to the untrained eye.

Red Rover, Red Rover—Send an Inspector Over

"Kids are always curious, asking what you’re doing, and you assure them that you’re helping out,” he says. “You seem to be the Pied Piper when you come, especially when you bring these funky gauges and probes with you.” When parents inquire, he has a chance to share that the community is thinking about playground safety. “I think they appreciate that,” he adds.

For a playground safety audit, Malkusak makes sure everything is up to current standards and guidelines. An inspection program visit means he’ll make sure the playground is in working order, and offer ideas on preventive maintenance—similar to a maintenance program for a car or home appliance, Malkusak explains.

“For an audit, I’m bringing out these funky-looking gadgets to test for hazards,” he says, “I’m looking for head entrapments or something that may entangle a string from a hooded sweatshirt.” He also has a torso probe and a head probe that makes sure kids can’t get their heads caught in a space where their bodies could pass through. A tape measure helps determine “use zones”—the areas around play equipment.

“For an inspection, I’m bringing whatever tools are recommended by the manufacturers to repair and keep things in good working order,” he says, so his toolbox might include wrenches, S-hook pliers, a grease gun, and more.

To test the ground surface’s impact attenuation qualities—how well it would cushion a child’s head and prevent permanent or fatal injury—Malkusak uses a triax, a tripod with a metal bowling ball-sized sphere that records speed and velocity of a potential head injury from the height of the structure.

Inspectors also scout for anything that can jab or impale kids as they’re climbing or falling.

Of course, Malkusak’s job must sound like a dream career to any kid under the age of 10: He must test the play equipment out himself—and teaches his inspection students to do the same.

Once, while leading a safety inspection training, he noticed what looked like a shoe scratch or hairline crack on a plastic molded slide. He had one of the inspection students go down the slide, and the hairline crack opened up into a huge crack all the way through. “We could have had an entrapment hazard,” he says. “We do have to go over, under, and through the play equipment, and yes, sometimes we do have to play on it—do the swings, go down the slide—to decide whether the equipment is compliant.”

On playground inspections, he’s seen kids take a leashed dog down the slide, prompting him to consider the hazards of leash entanglements that would hurt pets as well as children. Another time on a safety awareness program, he witnessed a tire swing attached to a composite structure clock a young boy in the jaw as he was playing tag on the structure. “He went over like a ton of bricks, poor guy,” remembers Malkusak. “I’m sure that tire swing and that composite structure are no longer up and functional.”

Sometimes people think if you’re inspecting a playground, you’re only trying to find what’s wrong with it, explains Malkusak, but inspectors are also trying to find what’s right with it.

Capture the (Red) Flag

Such warning signs can include mis-installation, which can make structures unsteady. “If you’re off by even a quarter of an inch, it can throw things way out of kilter in that area or on another end,” he says. “If it’s a community build, you really have to be on your toes.” Because structures are designed to be level and even from the first post, measurements must be spot on.

Some red flags require a bit of detective work to figure out what manufacturers had in mind. At one playground, a movement piece that was a rocking boat was supposed to be accessible to children of all abilities. But Malkusak spied a gap greater than one inch between the ramp and the boat, which can trap a wheelchair wheel or other mobility aid. A call to the manufacturer cleared up the confusion—the maker explained that the gap was going by a guideline exemption similar to the platform gap at a train station. Malkusak noted in his report to the owner/operator his observation and the interpretation of the rules from the manufacturer so the owner could make an informed decision.

Another industry challenge is wear and tear—maintaining frequently used play equipment. That includes wear and tear on surfaces as well: Loose-fill surfaces can get displaced, and the binder in unitary surfaces can break down over time. Under swings, it takes a huge amount of effort to keep a layer of wood chips in place because children tend to drag their feet, explains Dwight Curtis, parks and recreation director of the City of Moscow, Idaho, also an education Ph.D. candidate who will soon defend his research on playground safety.

Playground safety is a holistic issue, explains Curtis, and it’s more than just the inspections—it’s the supervisors of the inspectors, the playground equipment, all the safety research, and the supervision on the playground. “All those pieces put together tell a whole different story than each one individually,” he says.

Simon Says: Keep Kids Playing

As playground inspectors and the CPSI program get smarter about keeping kids safe, designers and manufacturers are dreaming up new ways to nurture imaginations and challenge children. “Playground designers are getting so much more educated and people understand how important play is,” says Smith, who continues that many playgrounds now incorporate teamwork and interactive elements. Newer playgrounds are also including tic-tac-toe boards, sound, I Spy games, adventure elements, and more.

As playgrounds become safer through recalls and improved maintenance, the way we think about play is growing and changing, too.

Malkusak has even begun to move away from the term “playground”—which connotes a static post and deck equipment with safety surface and containment border—and instead favors “play environments” or “playscapes” that include plants, water elements, pathways, sand, and more.

He adds: “A child should have the opportunity—in an unstructured setting—to explore and challenge their abilities to the fullest.”