The parks and recreation movement is historically linked to the playgrounds and settlement houses of the late 1800s. Child labor, immigration, crowded urban conditions, and other social ills resulted in efforts by Joseph Lee, Jane Addams, and others to improve the lives and health of children. There was a growing recognition of park spaces as a value to adults, children, and families due to the interaction with nature and the healthy atmosphere. In the early 1900s, led by the example of President Theodore Roosevelt, a lifelong champion of the value and healthful benefits of vigorous activity, many cities began the process of planning for parks in their communities.

The parks and recreation movement is historically linked to the playgrounds and settlement houses of the late 1800s. Child labor, immigration, crowded urban conditions, and other social ills resulted in efforts by Joseph Lee, Jane Addams, and others to improve the lives and health of children. There was a growing recognition of park spaces as a value to adults, children, and families due to the interaction with nature and the healthy atmosphere. In the early 1900s, led by the example of President Theodore Roosevelt, a lifelong champion of the value and healthful benefits of vigorous activity, many cities began the process of planning for parks in their communities.

So, while park and recreation professionals rightly point to the value of the services provided, it is also true that the places where those services occur are of critical importance. Throughout the 1900s, American parks evolved from being primarily Continental designs of landscapes, vegetation, and natural features into spaces dominated by athletic fields and courts, swimming pools, campgrounds, and lakes with boating opportunities. The pendulum, however, has begun to swing back: Recent land acquisition and park design emphasizes retention of open spaces for passive activities, and even conservation sites featuring habitat management.

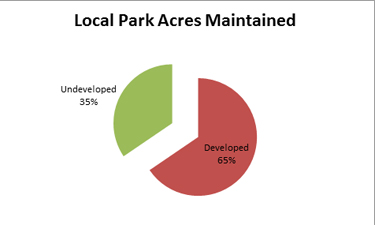

Today, municipalities, counties, special districts, and state parks manage and maintain over 20 million acres of land. State parks, with over 14 million acres, dominate both the acreage and the open space/conservation acreage. Yet the estimated 12,000 local park and recreation providers in the U.S. manage and maintain over 6.0 million acres. Of that acreage, 34.5 percent, or just over 2.0 million acres, are classified and managed as either open space (51.8 percent), conservation/managed habitat (43.3 percent), or preservation reserves (4.9 percent). Of perhaps greater significance, these 6.0 million acres are spread out so as to be accessible to over 80 percent of the national population. Thus, this mix of a three-vector strategy appears ready to survive well into this century. Park and recreation departments will continue to be expected to provide recreation programming, facility operations, and land management—including open space, conservation, and preservation lands.

Obviously, continued growth of recreation program participation levels will keep programming demand healthy, despite the need in some areas to distribute service provision to partners and individual entrepreneurs. Similarly, the uptick in participation in sports and related individual activities will maintain demand for the development of new active facility parks.

What is driving the demand for open space and conservation lands? Even in this time of economic constraints, bond referendums, specific levies for open-space management, local land trust easements, and other related programs are continuing to support land conservation.

At the turn of the twentieth century, society’s realization that the “frontier” was disappearing led to designation of national monuments, as well as game management areas and forests. In modern urban America, residents have been faced with infill developments that alter natural areas for residential or commercial development. Even when lands are privately owned, residents, accustomed to its natural character, object to its development. Unless the local government is willing to buy the property at market costs, the residents lose their “open space” and seek other sources as replacement.

One of those potential replacement locations in some urban areas are the brownfields or former industrial lands that have been environmentally cleaned and can now be used for renovation including replanting and management as an open space. A newer program called “redfields” is derived from the purchase and demolition of neighborhood residential housing that sells for reduced rates due to property foreclosure. These entire areas are subject to renovation and redevelopment, including the addition of parks and open spaces where none existed before. Finally, in many communities, strategies for walkable communities and related designs are resulting in built environments with a smaller footprint and the inclusion of open space and conservation lands in strategic proximity to the residential and commercial spaces, coupled with the green storm water runoff practices.

It is clear from the PRORAGIS national data above that departments that attain credibility in their communities as providers and managers of parks, recreation, open space, and conservation lands will be increasingly important assets--enriching their communities’ social, economic, and environmental sustainability.

Bill Beckner is NRPA's Research Manager.